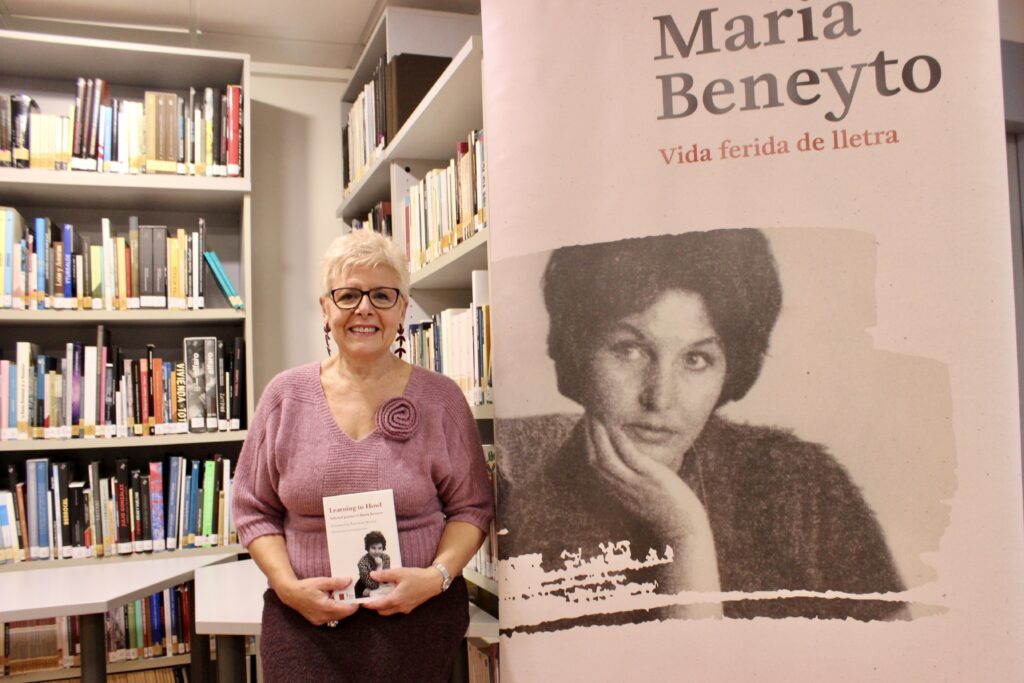

Last Friday, November 7th, the Library of El Poble Nou de Benitatxell hosted, thanks to Clásicas y Modernas, the ‘world premiere’ presentation of Learn to Howl, a compilation of 49 poems by María Beneyto translated into English by University of Valencia professor Paul Scott Derrick. The event was led by Carme Manuel Cuenca, president of the María Beneyto Commission of the Valencian Academy of Language. We had the opportunity to talk to her about the Year of María Beneyto and the extensive legacy that the AVL has left us about the writer.

As president of the Maria Beneyto Commission, what does it mean for the Acadèmia Valenciana de la Llengua to dedicate 2025 to María Beneyto, and what is the main objective of this commemoration?

María Beneyto is one of many writers honoured by the Acadèmia Valenciana de la Llengua. In 2021, the writers to whom the commemorations would be dedicated in the coming years were chosen: Joan Fuster for 2022, Valencian writers in exile for 2023, María Ibars for 2024, and María Beneyto for 2025.

We always want to make the appointment coincide with an anniversary, such as a centenary. At that time, we thought that María Beneyto was born in 1925, but when we began to investigate in the commission made up of Àngels Gregori, Vicenta Tasa, Ramon Ferrer and myself, we began to see that there was a difference between what the books and she herself said and the documents we began to find, thanks also to the help of our friends Helena Malonda, Vicente Malonda and Andrés Bolinches. That is why this year, which was originally supposed to be her centenary, is not. It is a tribute to the writer’s literary career. We have placed great emphasis on this in our presentations and publications.

Last year, we began to look at what activities we would do during 2025. One of the main activities is the travelling exhibition Maria Beneyto, vida ferida de lletra (Maria Beneyto, life wounded by letters), which has been touring town halls, cultural centres, libraries, secondary schools, etc. Until October 31st, it has visited 100 locations throughout the region. The text for the exhibition was written by Josep Ballester, and Suso Pérez and Ricardo Cañizares, designers from the company Gimeno Gràfic, were responsible for creating the panels. The exhibition is also accompanied by a brochure. This initiative is common to all the writers of the year. As president, I have visited many centres where it has been exhibited to present the exhibition.

We have also published the comic Maria Beneyto, passió per l’escriptura (Maria Beneyto, passion for writing), with a script by Raquel Ricart and illustrations by Daniel Olmo. A comic is always made about the writer of the year with the objective of having a publication that we can give away at all Valencian book fairs and events, as well as to any organisations that request it. The comic is addressed to schoolchildren, from secondary school to Baccalaureate, but also to adults. Raquel Ricart, as a good writer, did a lot of research to be able to summarise the most important points of María Beneyto’s life and work in these few pages. All of this is available to interested parties on the Academy’s website and is accompanied by an educational guide written by Professor Mireia Ferrando, which is mainly for teachers.

These are, so to speak, the crown jewels that have always been produced, although each committee then designs its own events. The María Beneyto Committee has had a serious budget problem, because we have not been able to count on financial support similar to that of other committees due to cutbacks. Even so, I believe we have carried out many activities, events, presentations, etc. I must say that the generosity shown by all the friends of the Academy has been invaluable.

Among other initiatives and actions we have carried out, we would highlight the literary route in Valencia created by Professor Àlex Bataller, featuring 12 locations where Beneyto lived or which are evoked in her literature. We will hold a preview on November 29th with Wikipedians. We have also collaborated on two important exhibitions in the city of Valencia, one at the MUVIM curated by Carmen Velasco and another at La Nau curated by Josep Ballester.

We have also organised an exhibition of unpublished photographs at the Railowsky bookshop, and we have also collaborated on a conference on the geography and city of Valencia, organised by Josep Vicent Boira and Valencia City Council, with two round tables on literature and floods. María Beneyto published a book in 1960 about the floods of 1949 and 1957, El río viene crecido (The River is Rising), and we talked about how she had dealt with this subject, but also about how current writers refer to it, or worse, do not refer to it.

Another thing we have done is the translation into Valencian of El río viene crecido (El riu ve crescut). I think it is the only book that needed to be translated into Valencian. Its protagonists are characters from marginalised Valencia in the late 1940s and 1950s. When you read them, you feel that they cannot speak Spanish, they have to speak Valencian. The book has been very well received and we are very happy about that. It was published by the Alfonso el Magnánimo institution, Drassana and the Acadèmia Valenciana de la Llengua. We are now in our second edition and will probably reach the third by Christmas.

I must say that Beneyto’s text had already been translated by early September 2024. Sometimes, that’s how tragic coincidences happen… Honestly, I don’t know if a novel will ever be written about the 2024 flood, but I think it would be very difficult to write another book like El río viene crecido. It is true that Beneyto goes far beyond what is a story about a flood or any other catastrophe. She is a writer who approaches reality to show the injustices and suffering of the most vulnerable people. Beneyto is interested in floods because the disasters caused by nature to the people of Valencia are preventable with good political planning. And the consequences of injustice are always paid for by the same people. They never have a way out. And this is precisely what she denounces. What is painful to her. I sincerely believe that it will be difficult for anyone to write something of such high quality that shakes the soul of readers. Time will tell.

We have then published Learning to Howl, an English translation of 49 poems, which we presented for the first time worldwide here at El Poble Nou de Benitatxell Library. The translation was done by Paul Scott Derrick, who is the translator of all Enric Valor’s fables into English. All the poems are accompanied by a series of drawings created by students from the illustration group at Benlliure Institute in Valencia, tutored by teacher Carmen Saura.

We have also retrieved an unpublished novel called Al llímit de l’absurd, which is very important because it shows that María Beneyto, until the last moments of her life, was interested in publishing again in Valencian, since until now we only knew La dona forta from 1967.

Not only have we published unpublished works, but we have also collected academic studies. In the Revista Valenciana de Filologia, we have a dossier with 12 articles; in December, we will publish dossiers in the magazines Saó and Caràcters. Caràcters will include more than 15 articles by scholars on María Beneyto and post-war writers from Alicante. This is a field that is completely unknown to the vast majority of the writer’s readers. In Saó, more than twenty women will talk about their literary relationship with Beneyto.

El Poble Nou de Benitatxell Council, in collaboration with Clásicas y Modernas, has held a series of events dedicated to Beneyto, including an introductory presentation, a reading club and a special session at the Literary Festival. How important is it for the AVL that local councils are involved in this way in promoting the year dedicated to the writer?

It is absolutely vital and fills us with joy and hope, because the Acadèmia is a public institution and, therefore, our vocation is one of public service. If what we do remains within the four walls of Sant Miquel dels Reis, it is a total failure.

If the AVL’s María Beneyto Year has been a success, it is because we have done everything we can to bring Beneyto to all kinds of venues: municipalities, schools, reading clubs, even a prison… any cultural or social organisation that has welcomed us, because not all of them can or want to welcome us. All we do is try to raise awareness and promote our writers, in this case Maria Beneyto. Therefore, we are always grateful to all the municipalities. We have been to El Poble Nou de Benitatxell twice, so our gratitude is doubled.

Like so many friends we have met throughout this year, our role is to “plant seeds”.

The poetry collection Learning to Howl has been presented at El Poble Nou. As an expert, what would you say to a reader approaching Beneyto’s poetry for the first time? Is there a recurring theme or style that you consider essential to highlight?

To get to know Maria Beneyto’s poetry means reading her work in Valencian, but also in Spanish. The complete compilation published by Rosa Mª Rodríguez Magda in 2008 is over 1,200 pages long. Beneyto did not want to write poetry, but rather “good” poetry, and she does so because, since her first collections in the early 1950s, she has been recognised as a poet of the first order. The themes that interest her are social and vindictive, such as the memory of her childhood as she experienced it, a time linked to the tragedy and suffering of the Civil War and the post-war period. This metaphorical universe features her father, her relationship with her mother, but above all, the compassion she feels for the dispossessed of the earth. In fact, social concern is the backbone that runs through all her poetry and is accompanied by a profound vision of female identity as a “multiple creature”. It is a vindication of the internal struggle between desire and the limitations of imposed social roles.

Maria Beneyto defined herself as self-taught, that is, without a higher education to support her, but she was a very good reader and a woman of extraordinary ambition. She reworks, experiments and is aware of her own growth throughout her career. This is evident, for example, when she rejected the first book published in 1947 and, a few years later, said that these were youthful experiments. She was very aware that the poetry she wrote was evolving.

I would also recommend reading her fiction. The stories are absolutely excellent. In poetry, sometimes you have to read between the lines. But in fiction, she is more explicit. In fact, El río que viene crecido is a political novel, an open denunciation of Franco’s autocratic Valencia of the 1940s and 1950s, and one in which there are many similarities with the present day.

Now that the event at El Poble Nou de Benitatxell has come to an end, what are the next major milestones for the María Beneyto Commission of the AVL, and how do you hope to continue the author’s legacy beyond 2025?

I am very pleased to say that on November 19th we will be going to Córdoba to give a presentation on María Beneyto, because her father was secretary of the UGT Peñarroya-Pueblonuevo, hosted by the Council and the Municipal Library of this town. As we discovered in the latest book published thanks to Rosa Mª Rodríguez Magda in 2019, Beneyto says that she did not spend the happiest years of her childhood in Madrid, but in this Andalusian town. Let’s take María Beneyto beyond our borders.

On November 25th, we will organise a conference on María Beneyto and cinema in post-war Valencia. And on December 3rd, we will be at the Women’s Library with an exhibition by Adriana Cembrero, a student who has created a magnificent photobook on the poetry collection Criatura múltiple (1954).

I am also pleased to announce that on December 14th we will be going to Muro d’Alcoi. Toni Espinar, who is an extraordinary muralist, painted a wonderful mural with portraits of many Valencian writers, including María Beneyto. The mural bears the date 1925-2011. In conversation with the Council and Toni Espinar, we suggested the possibility of organising an event to correct the year of birth. We will try to make it a big party and, above all, I am hoping that Helena Malonda and her father, Vicente Malonda, will be there, as well as Andrés Bolinches, who are the people who have helped us to register the church records of Oliva and to find out exactly who María Beneyto’s paternal family was.

Finally, we will end where we believe Maria Beneyto’s future will begin, at a nursery school, El trenet de Patraix. On December 18, the children will be learning some of Beneyto’s Christmas verses to symbolically convey the idea that we start with the youngest members of society and that our future will also depend on these children who, hopefully, at some point in their lives, will remember that María Beneyto is part of our culture.

This entire legacy is a source of hope and excitement. We want to believe that something will remain of everything we have done and that, after 2025, María Beneyto will be remembered forever. The books are there and the publications will remain on the website. That is our hope and our legacy.

What message would you send to the Council, Clásicas y Modernas and the residents of El Poble Nou de Benitatxell for hosting and participating so actively in the María Beneyto Year?

The María Beneyto Commission is very grateful for the welcome we have received at El Poble Nou de Benitatxell, both in August and now in November. The enormous satisfaction we feel for the support and friendship of all of you in these times of such uncertainty gives us a lot of strength and encouragement to keep going.